Section2.4Anagrams

¶An anagram of a word is another word (or sometimes many words) which is built up from the letters of the original, using each letter exactly once. For example an anagram of ‘retinas’ can be ‘nastier’, ‘retains’, or ‘stainer’. Even ‘sainter’ is a meaningful anagram (means trustworthy). One can even form anagrams using multiple words, like ‘tin ears’ or ‘in tears’.

We are interested in the number of anagrams a word can have. Of course, the number of all meaningful anagrams would be very hard to find, because some expressions can be meaningful to some, and not to others. For example, Oxford English Dictionary only contains the following anagrams of ‘east’: ‘a set’, ‘east’, ‘eats’, ‘sate’ (i.e. satisfy), ‘seat’, ‘teas’. Nevertheless, there is meaning given to all possible anagrams of ‘east’ in Ross Eckler's Making the Alphabet Dance. 1 Ross Eckler, Making the Alphabet Dance, St Martins Pr (July 1997)

In any case, how many possible anagrams are there for the word ‘east’? Let us build them up: for the first letter we have 4 choices, then we have only 3 choices for the second letter, we are left only with two choices for the third letter, and the not chosen letter will be the forth. That is, altogether there are \(4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 = 4! = 24\)-many anagrams. This is exactly the number of permutations of the four letter ‘a’, ‘e’, ‘s’ and ‘t’.

(Here we did not count the spaces and punctuations. It is possible that by clever punctuations one can make more of these. For example ‘a set’ and ‘as ET’ are both anagrams with the same order of letters, but with different meaning.)

To make matters simple, from now on we are only interested in the not necessarily meaningful anagrams, without punctuations. Thus, ‘east’ has 24 anagrams.

How many anagrams does ‘retinas’ have?

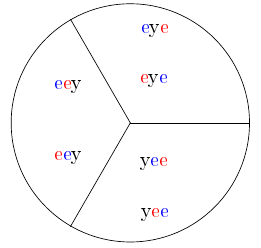

Now, let us count the number of anagrams of ‘eye’. There are only three of them: ‘eye’, ‘eey’, ‘yee’. Unfortunately, exactly the same argument as before does not work in this case. The complications arise because of the two e's: that is, those two letters are the same. We could easily solve the problem if the two e's would be different. Thus let us make them look different. Let us colour one of the e's by blue, the other e by red, and consider all coloured anagrams. Now, every letter is different, and the former argument works: there are \(3\cdot 2 \cdot 1 = 6\) coloured anagrams. Nevertheless, we are interested in the number of anagrams, no matter their colour. Therefore we group together those anagrams, which represent the same word, only they are coloured differently (see Figure 2.4.2).

Now, we are interested in the number of groups. For that, we need to know the number of anagrams in one group. Take for example the group corresponding to the anagram ‘eye’ (upper right part). There are two different colourings depending on the e's: we can colour the first ‘e’ by two colours, and the second ‘e’ by one colour, therefore there are \(2 \cdot 1 = 2\) coloured ‘eye’s in that group. Similarly, every group contain exactly two coloured anagrams. Thus the number of groups (and the number of uncoloured anagrams) is \(\frac62 = 3\text{.}\)

Exercise2.4.3

How many anagrams does the word ‘puppy’ have? Try to use the argument presented above.

This argument can now be generalized when more letters can be the same:

Theorem2.4.4

Let us assume that a word consists of \(k\) different letters, such that there are \(n_1\) of the first letter, \(n_2\) of the second letter, etc. Let \(n = n_1 + n_2 + \dots + n_k\) be the number of letters altogether in this word. Then the number of anagrams this word has is exactly

\begin{equation*} \frac{n!}{n_1! \cdot n_2! \cdot \dots \cdot n_k!}\text{.} \end{equation*}Proof

Let us color all the letters with different colours, and let us count first the number of coloured anagrams. This is the number of permutations of \(n\) different letters, that is, \(n!\) by Theorem 2.3.3.

Now, group together those anagrams which represent the same word, and differ only in their colourings. The number of uncoloured anagrams is the same as the number of groups. To compute this number, we count the number of coloured words in each group.

Take an arbitrary group representing an anagram. The words listed in this group differ only by the colourings. The first letter appears \(n_1\)-many times, and these letters have \(n_1!\)-many different colourings by Theorem 2.3.3. Similarly, the second letter appears \(n_2\)-many times, and these letters have \(n_2!\)-many different colourings by Theorem 2.3.3, etc. Finally, the \(k\)th letter appears \(n_k\)-many times, and these letters have \(n_k!\)-many different colourings by Theorem 2.3.3. Thus, the number of words in a group is \(n_1! \cdot n_2! \cdot \dots \cdot n_k!\text{.}\) Therefore the number of groups, and hence the number of (uncoloured) anagrams is

\begin{equation*} \frac{n!}{n_1! \cdot n_2! \cdot \dots \cdot n_k!}\text{.} \end{equation*}Exercise2.4.5

How many anagrams does the following expressions have?

‘college’,

‘discrete’,

‘mathematics’,

‘discrete mathematics’,

‘college discrete mathematics’.

Exercise2.4.6

Alice, Beth and Carrie are triplets. For their birthdays, they receive 12 bouquets of flowers, all of them are from different flowers. They decide that Alice should choose 5 bouquets, Beth should choose 4 bouquets, and Carrie takes the remaining 3 bouquets. How many ways can they distribute these 12 bouquets?